“Let’s see what he’s got,” Snowell thought to himself, and he and his group picked up their pace, moving in on the challenger. Tyson shrugged and responded with an odd sentiment for an unbeaten and seemingly indestructible fighter: “If I get my butt whipped, I’ll take the blame.” Once in Tokyo, Snowell and others in the Tyson camp went out for some early morning roadwork-without Tyson himself!-and came upon a solitary runner up ahead: Douglas. Tyson’s lead trainer, Aaron Snowell, presciently told him that he was in real trouble if he didn’t start getting serious in training. We learn that Tyson’s deservedly maligned cornermen-who lacked even rudimentary equipment to help their fighter on what became his most desperate night-were at least competent enough to worry about the champion’s lack of interest in the Douglas bout. Though the basic narrative of the Tokyo fight is familiar, Layden fills it in with fascinating and little-known detail, the product of interviews with fighters, trainers, the HBO commentators, and other boxing insiders. When boxing reaches its rare pinnacles, as it did in Tyson-Douglas, it can seem to a fan like the only thing worth paying attention to. But Layden understands what boxing commentators like Larry Merchant and Jim Lampley, who were ringside in Tokyo, know from years of calling fights, and what innumerable boxing writers and fans, too, have learned through their own devotion to the sport: that its dangerous, primitive theater is rich in character and pathos, drama and lore, in a way that no other athletic competition can match. Peopled with gamblers and ruthless, amoral promoters like Don King, the sport’s action involves two grown men apparently trying to do nothing more elevated than beat one another into submission. Without a heavyweight champion who captures public imagination, boxing is the sporting equivalent of a political third party: you’re always a bit surprised when someone you know is involved with such weirdness.

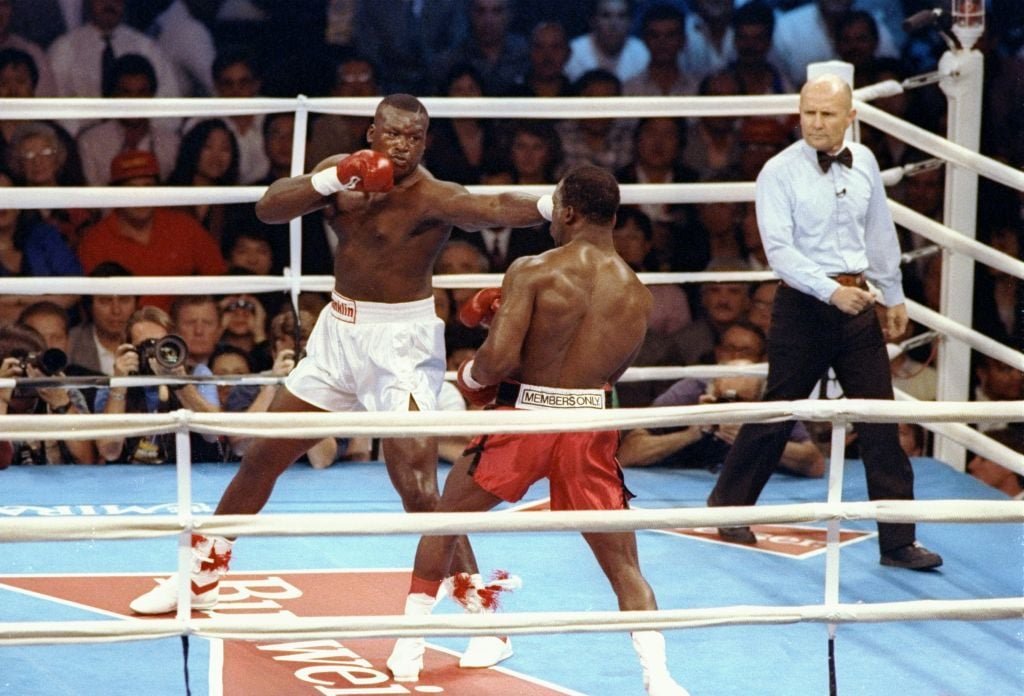

If his title is a bit of hyperbole-there have been great fights since, even if few of us have seen them-he’s certainly right in his larger point: Tyson’s defeat that night was really the beginning of the end of boxing’s last period of glamour. Joe Layden’s The Last Great Fight tells the story of Tyson and Douglas and that memorable evening in Tokyo when the impossible-but now, in retrospect, the inevitable-happened. Tyson was a fixture in the pop culture, a character in video games and commercials, a frequent presence on magazine covers, and-of late-in tabloids, as his life slowly unraveled into a circus sideshow. Most of his opponents came into the ring already beaten mentally, looking for a place to fall. He was expected to have a long reign as champion and take his place in the pantheon of boxing greats like Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali, and others whose names were less known to casual fans, but whose deeds Tyson had studied for years in old black and white films. Tyson was only 23 years old he was undefeated in 37 fights all but a few of his wins came by knockout, most of those in the early rounds, sometimes in the first few minutes or even seconds. That’s the kind of allure Mike Tyson had from the very beginning, and certainly in 1990, when he lost to Douglas in a monumental sports upset that few had seen coming. Paging through the magazine on a commuter train, I was interrupted by a man seated behind me, who asked, “Do you mind if I just look over your shoulder?” Soon a small crowd of men had gathered around, doing the same. In the days before the Internet, such a production was eagerly awaited.

In February 1990, a few days after Mike Tyson lost the heavyweight championship to James “Buster” Douglas in Tokyo, Sports Illustrated showed the fallen boxer on its cover and ran a photo spread and report inside. The Last Great Fight: The Extraordinary Tale of Two Men and How One Fight Changed Their Lives Forever, by Joe Layden (St.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)